Last month I was wondering if there were any Christmas songs in minor keys besides "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen." I suspected "We Three Kings of Orient Are," but when I sat down at my keyboard and played through it, I discovered that it's not that straight-forward. The verses are in a minor key, but the choruses are in a major key (the relative major of the minor key).

The only recording I have of "We Three Kings of Orient Are" is the Beach Boys' version, so I referenced that and figured out the vocal melody. Here's the melody for the verses, in F# minor:

And here's the melody for the choruses, in A major:

The minor key doesn't have implications for all of the verses, but for the first (along with the alliterative catalogue of "Field and fountain, moor and mountain"), it suggests the weariness of lengthy travel ("we traverse far... Following yonder star"). The turn to the major key for the chorus almost gives a sense of the joy and enlightenment that the kings receive from the "star of wonder" that "Guide[s] us to the perfect light."

While thinking about the melody, I also realized that its being in 3/4 is significant. There are three beats in each measure, and the song is about three kings.

Monday, December 18, 2017

Monday, December 11, 2017

Bill Haley & His Comets' What a Crazy Party: The Best of the Decca Years

A couple months ago, I listened to a two Bill Haley albums a few times each: From the Original Master Tapes and What a Crazy Party: The Best of the Decca Years, which contains four original albums alongside some singles (I should note that all of the tracks on From the Original Master Tapes are also on What a Crazy Party). I found a number of things to write about, but since they're mostly small points, I thought I'd write a post about the collection as a whole.

For what it's worth, the title What a Crazy Party comes from a line in this song.

The phrase at the end of "Burn That Candle" (played on saxophone) is something like:

And here's the phrase from Mendelssohn's Wedding March that it quotes:

That's just the first violin part, but the same phrase is played on the flutes, oboes, and clarinets.

There are only slight differences between Mendelssohn's phrase and this quotation. The rhythms are basically the same (the phrase in "Burn That Candle" just turns some of Mendelssohn's quarter notes into pairs of eighth notes), and with the exception of one note (the third in each phrase), the intervals are the same.

Recently, however, I noticed that there's an-other phrase that seems to come from the Wedding March. After the first chorus and the saxophone solo, there's this five-note phrase:

These are the same four notes that begin the Wedding March quotation at the end, just an octave lower and with the order of two notes (E and D) reversed.

"Dim, Dim the Lights (I Want Some Atmosphere)"

I actually noticed a couple months ago that the line "Turn down the lights" descends (I think it's E C C# A), as if to match the lowering of the light level, but I didn't think that that alone was significant enough to write a post about.For what it's worth, the title What a Crazy Party comes from a line in this song.

"Burn That Candle"

At the very end, there's a near quote of Mendelssohn's Wedding March from the incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream (Op. 61). I probably noticed this quotation before but didn't really think about it.The phrase at the end of "Burn That Candle" (played on saxophone) is something like:

And here's the phrase from Mendelssohn's Wedding March that it quotes:

|

| [notation found here] |

That's just the first violin part, but the same phrase is played on the flutes, oboes, and clarinets.

There are only slight differences between Mendelssohn's phrase and this quotation. The rhythms are basically the same (the phrase in "Burn That Candle" just turns some of Mendelssohn's quarter notes into pairs of eighth notes), and with the exception of one note (the third in each phrase), the intervals are the same.

Recently, however, I noticed that there's an-other phrase that seems to come from the Wedding March. After the first chorus and the saxophone solo, there's this five-note phrase:

These are the same four notes that begin the Wedding March quotation at the end, just an octave lower and with the order of two notes (E and D) reversed.

"Hey Then, There Now"

One of the verses ends with the line "Will you be the apple of my eye?" which is a phrase from the Bible. It's in Psalm 17:8 ("Keep me as the apple of your eye; hide me in the shadow of your wings"), but apparently the first instance is Deuteronomy 32:10: "He [God] found him [Jacob] in a desert land, and in the howling waste of the wilderness; he encircled him, he cared for him, he kept him as the apple of his eye.""How Many?"

I noticed a couple things about the bridge:Now there must have been a million

For everywhere you go

You seem so well acquainted

Ev'rybody says hello

The "every-" of "everywhere" is pronounced with three syllables (rather than just two, like the "ev'ry-" of "ev'rybody"). This three-syllable pronunciation provides a sense of the breadth of everywhere.

I also noticed a grammatical ambiguity: for could be understood as preposition or a conjunction. As a preposition, there's a sense of calculating. With that parsing, the sentiment is: you've surely known a million guys in each place you've been. Parsing for as a conjunction provides a reason for positing that "there must been been a million." It's easier to see the distinction if for is replaced with because: "Now there must have been a million [guys you know] / Because everywhere you go / You seem so well acquainted."

"Rock Lomond"

The last verse begins with the lines "Now you take the high road / And I'll take the low road." The "take the high road" ascends (G A B B), and "take the low road" descends (A G E D). Each phrase is sung to a melody that musically illustrates the height of the road described."Rip It Up"

I noticed years ago that the saxophone solo starts with a phrase from "Santa Claus Is Coming to Town." It's a variation on the melody to which "You better watch out; you better not cry / You better not pout" is sung."Skinny Minnie"

The first verse ends with the line "Well, she is the apple of my eye," which - as I mentioned above with "Hey Then, There Now" - is a phrase from the Bible.Friday, December 8, 2017

The Byrds' "Oh, Susannah"

A month or two ago, I started practicing Stephen Foster's "Oh! Susanna" in my piano book (The Older Beginner Piano Course, Level 2 by James Bastien). It reminded me of the Byrds' version (with a slightly different title: "Oh, Susannah") on Turn! Turn! Turn!, so I compared the music in my book with the Byrds' recording.

Here's the rhythm as it is in my piano book (I had to squeeze the top line a bit to accommodate the up-beat). It's in G major in my book, but I transposed it to F major because that's the key the Byrds' version is in:

The Byrds' version alternates between instrumental sections (where the melody is played on twelve-string guitar) and sections that are sung. There are three of these instrumental sections, and the first and third are the same (the guitar part is, at least), but the second is slightly different. Here's the notation for the first and third iterations:

Compared to Foster's rhythms, the Byrds' version is more syncopated. In the third measure in each line, two of Foster's quarter notes are turned into a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note, and there's a similar shift in rhythm in the second measure of the third line.

That second measure of the third line is the only difference in the second iteration of the instrumental section. In the first and third iterations, there's a half note tied to an eighth note followed by a second eighth note, but in the second, it's a dotted half note:

In my piano book, the song is played with only three chords (I, IV, and V7), ostensibly because it's a book for beginners. The Byrds' version of "Oh, Susannah," however, involves six chords (played only during the sections that are sung):

F major | A minor | D minor | G major

F major | A minor | D minor | G major | F major

Bb major | F major | C major

F major | A minor | D minor | G major | F major

The coda is Bb major to F major.

Here's the rhythm as it is in my piano book (I had to squeeze the top line a bit to accommodate the up-beat). It's in G major in my book, but I transposed it to F major because that's the key the Byrds' version is in:

The Byrds' version alternates between instrumental sections (where the melody is played on twelve-string guitar) and sections that are sung. There are three of these instrumental sections, and the first and third are the same (the guitar part is, at least), but the second is slightly different. Here's the notation for the first and third iterations:

Compared to Foster's rhythms, the Byrds' version is more syncopated. In the third measure in each line, two of Foster's quarter notes are turned into a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note, and there's a similar shift in rhythm in the second measure of the third line.

That second measure of the third line is the only difference in the second iteration of the instrumental section. In the first and third iterations, there's a half note tied to an eighth note followed by a second eighth note, but in the second, it's a dotted half note:

In my piano book, the song is played with only three chords (I, IV, and V7), ostensibly because it's a book for beginners. The Byrds' version of "Oh, Susannah," however, involves six chords (played only during the sections that are sung):

F major | A minor | D minor | G major

F major | A minor | D minor | G major | F major

Bb major | F major | C major

F major | A minor | D minor | G major | F major

The coda is Bb major to F major.

Monday, December 4, 2017

Peter & Gordon's "I Don't Want to See You Again"

I recently learned the chords for Peter & Gordon's "I Don't Want to See You Again" (credited to Lennon-McCartney although apparently written by McCartney alone) and I found some connections between the lyrics and certain chords.

Here's the chord progression (with - as always - the disclaimer that I might have something wrong):

Introduction

C minor | G major

Verses

G major | B minor | C minor | D major

G major | B minor | C minor | G major

Bridge

|: C major | G major :| E minor

A minor | B major | E minor

A minor | D major

Here's the chord progression (with - as always - the disclaimer that I might have something wrong):

Introduction

C minor | G major

Verses

G major | B minor | C minor | D major

G major | B minor | C minor | G major

Bridge

|: C major | G major :| E minor

A minor | B major | E minor

A minor | D major

The song is in G major, so that C minor chord (with its Eb accidental) is an outlier. Most of the titular line (all but the last syllable of "again") is sung above this C minor, so there's a musical tension attached to this sentiment. Furthermore, one of the vocal melodies sings "I don't want to see" to an A note. Combined with the Eb in the C minor chord, this forms a tritone, a dissonant feature that adds to the musical strain.

This odd C minor is also the chord beneath the phrase "Something wrong." The foreign tonality demonstrates the "something wrong." The second half of this line is "could be right," and the chord progression moves to a D major. Since D major is the dominant chord in G major, the "right"ness of tonality is restored.

The beginning of the bridge alternates between C major and G major chords, but at "day" in "You hid the light of day," the progression moves to E minor. The sadness associated with minor chords connects to the loss of "the light of day" mentioned in the lyrics.

Monday, November 27, 2017

Simon & Garfunkel's "Blessed"

Last week I listened to Simon & Garfunkel's Sounds of Silence for the first time in over a year, and I remembered something I'd previously noticed but (apparently) haven't written about: the song's verses have the same structure as the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12). Each Beatitude has the structure "Blessed are [group] for...." The first three lines of each verse in "Blessed" begin with either "Blessed are..." or "Blessed is...." For instance, the first line of the song is "Blessed are the meek for they shall inherit," which is almost straight from Beatitudes. It's just missing the direct object of "inherit" - "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth" (Matthew 5:5).

I'd noticed that similarity years ago, but when I listened to the song again recently, I found an-other Biblical reference. Each verse ends with the line "Oh, Lord, why have you forsaken me," which is similar to the first half of Psalm 22:1: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" This verse is also quoted by Christ on the cross (Matthew 27:46, Mark 15:34).

I'd noticed that similarity years ago, but when I listened to the song again recently, I found an-other Biblical reference. Each verse ends with the line "Oh, Lord, why have you forsaken me," which is similar to the first half of Psalm 22:1: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" This verse is also quoted by Christ on the cross (Matthew 27:46, Mark 15:34).

Monday, November 20, 2017

The Moody Blues' Keys of the Kingdom

Last month I read Matthew 16:19, where Jesus tells His disciples "I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven." This reminded me of the Moody Blues album Keys of the Kingdom, and I started wondering whether this verse had any influence on the album title. I listened to Keys of the Kingdom a few days ago, and while I didn't find anything that connects it to this verse from Matthew, I did find a couple things to write about.

"Bless the Wings (That Bring You Back)"

The last three lines of the bridge are "The dust of many centuries / Has blown across this land / But love will not be scattered like the sand." These are fairly similar to the bridge of "Lovely to See You" from On the Threshold of a Dream: "Tell us what you've seen in faraway forgotten lands / Where empires have turned back to sand." There are a number of similarities here: both songs were written by Justin Hayward; both of these sections are bridges; and both rhyme "land(s)" with "sand."

A couple months ago I wrote a post about the bridge in "Lovely to See You" and postulated that it might have been influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Ozymandias," which has the same image of a domain erased by sand and even the same land/sand rhyme. This same image appearing again in "Bless the Wings" (although this time with love surviving) could be coincidental, or it might be Hayward's revisiting either his older song or Shelley's poem.

A couple months ago I wrote a post about the bridge in "Lovely to See You" and postulated that it might have been influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Ozymandias," which has the same image of a domain erased by sand and even the same land/sand rhyme. This same image appearing again in "Bless the Wings" (although this time with love surviving) could be coincidental, or it might be Hayward's revisiting either his older song or Shelley's poem.

"Once Is Enough"

A year or two ago I noticed that the Moody Blues reference themselves at the beginning of the second verse. According to the lyrics printed in the liner notes:

Listening to the song again recently, I noticed something besides this allusion. The first line is "Just ask me once," and it's sung by a single voice. The second line is "Don't ask me twice," and it's sung by two voices. In those two lines, the number of voices singing is a musical representation of the "once" and "twice."

Sometimes you're firstDays of Future Passed is the title of the Moody Blues' second album.

Sometimes you're last

Then again you're somewhere

In your "days of future passed"

Listening to the song again recently, I noticed something besides this allusion. The first line is "Just ask me once," and it's sung by a single voice. The second line is "Don't ask me twice," and it's sung by two voices. In those two lines, the number of voices singing is a musical representation of the "once" and "twice."

Monday, November 13, 2017

The Lovin' Spoonful's "Younger Girl"

An-other thing I noticed while listening to a compilation album of the Lovin' Spoonful last month is the ending of "Younger Girl." The lyric at the end is the same as at the beginning:

She's one of those girls who seems to come in the spring

One look in her eyes and you forget ev'rything you had ready to say

Where the introduction completes this with "And I saw her today, yeah" and then continues with the rest of the song, the coda fades out part-way through the "One look in her eyes..." line. Fading out during that line gives an impression of what the line itself describes: "forget[ting] ev'rything you had ready to say." It's as if the song itself gets distracted by "one of those girls," forgets what it's doing, and just trails off.

Monday, November 6, 2017

The Lovin' Spoonful's "Did You Ever Have to Make up Your Mind?"

A couple weeks ago, I listened to a compilation album of the Lovin' Spoonful and noticed something about "Did You Ever Have to Make up Your Mind?" specifically these two sections:

Sometimes there's one with big blue eyes, cute as a bunny

With hair down to here and plenty of money

And just when you think she's that one in the world

Your heart gets stolen by some mousy little girl

Sometimes you really dig a girl the moment you kiss her

And then you get distracted by her older sister

When in walks her father and takes you in line

And says, "Better go home, son, and make up your mind"

For each line in these two sections - and within the last line of the second section - there's a different singer or combination of singers. There's a constant musical shifting in the same way that "your heart gets stolen" or "you get distracted" by the allure of sundry girls.

Monday, October 30, 2017

George Harrison's "Devil's Radio"

I recently listened to George Harrison's Cloud Nine, and I rediscovered that one guitar phrase in "Devil's Radio" (first present at about 0:29) sounds similar to a guitar phrase in the Beatles' "It Won't Be Long" (first present at about 0:26, when the verse transitions to the chorus). I'd discovered this similarity in 2014; however, I hadn't lookt into the music back then. This June, I learned some of the guitar phrases in "It Won't Be Long" for my Beatle Audit project, so all I had to do was learn the phrase in "Devil's Radio" and compare them.

Tonally, the phrases are exactly the same; the only difference is in the rhythm and articulation:

A few caveats on my notation: 1) these are both notated an octave higher than played, in order to avoid a mess of ledger lines below the staff, 2) for both examples, I'm not sure if the last note is specifically a half note; it might be longer or shorter, 3) there's a glissando at the end of the phrase in "Devil's Radio," so where my notation has a single C#, it's really a B slid into a C#, but the B is negligible as far as note values.

One of the other songs on Cloud Nine is "When We Was Fab," which has lyrical and musical references to Harrison's days in the Beatles. Those references suggest that the similarity between these guitar phrases is intentional rather than coincidental.

Tonally, the phrases are exactly the same; the only difference is in the rhythm and articulation:

A few caveats on my notation: 1) these are both notated an octave higher than played, in order to avoid a mess of ledger lines below the staff, 2) for both examples, I'm not sure if the last note is specifically a half note; it might be longer or shorter, 3) there's a glissando at the end of the phrase in "Devil's Radio," so where my notation has a single C#, it's really a B slid into a C#, but the B is negligible as far as note values.

One of the other songs on Cloud Nine is "When We Was Fab," which has lyrical and musical references to Harrison's days in the Beatles. Those references suggest that the similarity between these guitar phrases is intentional rather than coincidental.

Monday, October 23, 2017

Andrew Bird's Are You Serious

I listened to Andrew Bird's Are You Serious a few times this month and found some things to write about.

"Capsized"

This is just a small point, but the various articulations of "falling" in the lines "Night's falling" and "Sky's falling" descend in pitch, so there's a musical falling to mirror the falling in the lyrics. Sometimes, the "falling" is even sung with a melisma, which emphasizes the effect."Puma"

As written in the liner notes (which differ a bit from the song itself), the lyrics for one section areWhen she was radioactive for seven daysThe backing vocals harmonize with the lead vocals for the ends of the first two lines ("seven days" and "anyway") and then repeat the "ay" sound of the rhyme, so there's a musical representation of the half-life of radiation. There's the initial "ay" sound in the lead vocals, and then it "decays" by moving to the backing vocals, where it "decays" even further by lowering in pitch (F# to E to D). Perhaps significantly, this feature isn't present for the "ay" of "away" because the singer/speaker is "stay[ing] away" from the radioactive girl.

How I wanted to be holding her anyway

But the doctors they told me to stay away

Due to flying neutrinos and

Gamma rays

"Left Handed Kisses"

This is an-other small point, but there's a fairly large musical interval between the notes in "To us romantics out here that amounts to" and those in "high treason." I think it's a fifth (A to E) between "that amounts to" and "high." In any case, the high musical note emphasizes the notion of "high treason."

"Saints Preservus"

The first line is "I once was found but now I'm lost," which is an inversion of sorts of "I once was lost but now am found," a line from "Amazing Grace."

A later line is "Bring me your poor and your trembling masses," which is a near quote of Emma Lazarus' "The New Colossus" (the poem written about and displayed in the Statue of Liberty). In Lazarus' poem, the lines are "Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

I think there might be a third allusion in the line "I'm a stranger in a land that's anything but strange." It has a similar structure to a pair of lines in the folk song "Wayfaring Stranger" (here's a link to the song in Roger McGuinn's Folk Den). Since it's a folk song, different versions of "Wayfaring Stranger" exist (including mine), but - as I'm familiar with it - the first two lines are "I am a poor wayfaring stranger / Wandering through this world of woe."

A later line is "Bring me your poor and your trembling masses," which is a near quote of Emma Lazarus' "The New Colossus" (the poem written about and displayed in the Statue of Liberty). In Lazarus' poem, the lines are "Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

I think there might be a third allusion in the line "I'm a stranger in a land that's anything but strange." It has a similar structure to a pair of lines in the folk song "Wayfaring Stranger" (here's a link to the song in Roger McGuinn's Folk Den). Since it's a folk song, different versions of "Wayfaring Stranger" exist (including mine), but - as I'm familiar with it - the first two lines are "I am a poor wayfaring stranger / Wandering through this world of woe."

"Bellevue"

The album is bookended with nautical imagery, which is in both "Capsized" (the first song on the album) and "Bellevue" (the last track on the album). The title line in "Capsized" is "This ship is capsized," but in "Bellevue," there's the line "Guides my lonely ships on through the shallows." The images themselves are opposites, but they're drawn from the same pool, as it were.

Monday, October 16, 2017

Don McLean's "Babylon"

I haven't found much to write about recently, so here's a short post about Don McLean's "Babylon" from the American Pie album. I recently learned and notated the vocal melody:

These twelve measures repeat, but the second half of the song is sung as a round so that these three lines are sung simultaneously among three voices.

As formatted in the liner notes, the lyrics are:

By the waters

The waters of Babylon

We lay down and wept

And wept for thee, Zion

We remember... Thee

Remember... Thee

Remember... Thee

Zion

In the liner notes, McLean comments that "the song was created in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1930s, and it was taken from one of the Psalms in the Bible." About two years ago, I discovered that it's Psalm 137:1: "By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion."

Monday, October 9, 2017

Mendelssohn: String Quartet in D major, Op. 44, No. 1

I listened to Mendelssohn's String Quartet in D major (Op. 44, No. 1) a few times last month, and some melodies in the second movement sounded familiar to me. Here's the first line:

(notation found here)

The first and second violin parts here bear strong resemblances to the hymn tune "Chesterfield" (used for "Hark the Glad Sound"). Last December, I recorded this tune for my blog about hymns:

(notation found here)

The first and second violin parts here bear strong resemblances to the hymn tune "Chesterfield" (used for "Hark the Glad Sound"). Last December, I recorded this tune for my blog about hymns:

The arrangements I used for my recording (I combined arrangements from Lutheran Worship [#29] and The Lutheran Service Book [#349]) are in F major, but here's the first phrase of "Chesterfield" transposed up an octave and into D major in order to compare it to the first few bars of the first violin in Mendelssohn's string quartet:

A few note values are different, but - with "Chesterfield" adjusted for key - the pitches are all the same.

Here's the second phrase of "Chesterfield" (again transposed to D major, but not transposed up an octave) and the second violin part from Mendelssohn's string quartet, starting from the sixth full measure:

These phrases are quite similar too. The last five notes here have the same intervals; while they start from different pitches, the melody goes down a half-step, up a half-step, down a minor third, and then down a whole-step.

I couldn't find much information about Mendelssohn's string quartet, just that it was composed in 1838. Likewise, I couldn't find a great degree of definite information about "Chesterfield." Either it was written by or is attributed to Thomas Haweis, who was born in 1732 or 1734 (sources vary) and died in 1820. According to Hymnary, the tune itself was published in 1792. While all of that is a bit shaky, it's clear that "Chesterfield" is older than Mendelssohn's string quartet.

I don't know if Mendelssohn was familiar with "Chesterfield," but the resemblance between it and this movement of his string quartet seems to suggest so. For what it's worth: this wouldn't be the only instance of Mendelssohn's using a hymn tune in his music. His Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 107, written in 1830, quotes Martin Luther's "Ein feste Burg."

Here's the second phrase of "Chesterfield" (again transposed to D major, but not transposed up an octave) and the second violin part from Mendelssohn's string quartet, starting from the sixth full measure:

These phrases are quite similar too. The last five notes here have the same intervals; while they start from different pitches, the melody goes down a half-step, up a half-step, down a minor third, and then down a whole-step.

I couldn't find much information about Mendelssohn's string quartet, just that it was composed in 1838. Likewise, I couldn't find a great degree of definite information about "Chesterfield." Either it was written by or is attributed to Thomas Haweis, who was born in 1732 or 1734 (sources vary) and died in 1820. According to Hymnary, the tune itself was published in 1792. While all of that is a bit shaky, it's clear that "Chesterfield" is older than Mendelssohn's string quartet.

I don't know if Mendelssohn was familiar with "Chesterfield," but the resemblance between it and this movement of his string quartet seems to suggest so. For what it's worth: this wouldn't be the only instance of Mendelssohn's using a hymn tune in his music. His Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 107, written in 1830, quotes Martin Luther's "Ein feste Burg."

Monday, October 2, 2017

Les Paul and Mary Ford's "Whither Thou Goest"

Last month, I listened to a three-CD set of Les Paul (with Mary Ford, although she's not credited), and I realized that the lyrics in "Whither Thou Goest" come from the Bible, specifically Ruth 1:16. The first verse of the song is:

Whither thou goest, I will goIt's taken almost directly from the King James Version:

Wherever thou lodgest, I will lodge

Thy people shall be my people, my love

Whither thou goest, I will go

And Ruth said, "Intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God."For what it's worth, here's a video that walks through the original Hebrew of the second half of the verse:

Monday, September 25, 2017

Del Shannon's "Two Silhouettes"

Last month, I learned the chords for Del Shannon's "Two Silhouettes" and noticed a feature with an accidental.

First of all, here are the chords (with the disclaimer that, as always, I might have something wrong):

Intro

|: C major | Bb major :|

First verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

Link

|: C major | Bb major :|

Second verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

F major | C major

Bridge

F major | C major

F major | G major | C major

F major

G major

Third verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

Tag

|: C major | Bb major :|

First of all, here are the chords (with the disclaimer that, as always, I might have something wrong):

Intro

|: C major | Bb major :|

First verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

Link

|: C major | Bb major :|

Second verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

F major | C major

Bridge

F major | C major

F major | G major | C major

F major

G major

Third verse

C major | A minor

F major | C major | G major

C major

F major | D major

|: C major | A minor :|

C major | G major | C major

Tag

|: C major | Bb major :|

The song is in C major, and - aside from the Bb major in the instrumental sections - the only chord with an accidental note is D major (with an F#). In two of the verses, the lyrics above this chord describe a change. In the first verse, the line there is "And all the rain seemed to turn to tears" and in the third verse, "I know things will never be the same." That F# accidental helps to musically portray the "turn" and not being "the same." One of the voices in the backing vocals even goes from an F natural to an F# during that line, emphasizing the accidental.

Friday, September 22, 2017

Del Shannon's "I Won't Be There"

I had to put some notes in a lower octave, and my double-tracking isn't exactly spot-on, but I still think it turned out pretty well.

Monday, September 18, 2017

Cliff Richard's "The Snake and the Bookworm"

Last month I figured out the bass part for Cliff Richard's "The Snake and the Bookworm," and I noticed a couple things about it. First of all, I discovered that the two copies of "The Snake and the Bookworm" in my music collection are different recordings. I have two compilation albums of Cliff Richard, and while there's a lot of overlap as far as songs, I've been discovering that some are different recordings. I referenced the version of "The Snake on the Bookworm" on a compilation titled The Early Years, which looks like this:

The bass part isn't very unusual for its era, but there are two features that I found interesting.

For most of the song, the bass arpeggiates the chords it's played beneath. There's the root, third, and fifth, and then it adds a sixth and a flatted seventh before descending, playing the same notes in reverse order. This is a standard feature in early rock and roll bass parts. However, underneath the Bb major, the bass forgoes the flatted seventh and instead plays the root an octave higher. Instead of

which would match the figures played underneath the F major and C major chords, it's

Musically, it makes the song more interesting, but it also demonstrates the character of the snake. This musical figure doesn't match the others in the same way that the snake seems to challenge authority and do whatever he likes. For three of its four occurrences, the lines above this figure describe the snake: "He tracks her down on the way to school," "And he wants to go and have some fun," and "And he's thinkin' 'bout his recreation." The only line above this figure that doesn't mention the snake still has a sort of rebellious element in that it features grammatical errors and mentions the possibility of failing a test: "Well, she got a test, and she don't wanna fail."

At the end of the instrumental section, the song changes keys from F major to F# major. This is a musical illustration of what happens in the third verse:

Similarly, the bass figure underneath the B major chords (formerly Bb major chords) now matches those underneath the F# major and C# major chords. They're all root, third, fifth, sixth, and flatted seventh. Because of the snake's change, the earlier "rebellion" of replacing that flatted seventh with the root played an octave higher has disappeared.

Here's the bass part in full, with the disclaimer that - as always - I might have something wrong:

|: F major | Bb major | F major :|

C major

Bb major

|: F major | Bb major | F major :|

Verse after key change:

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

|: B major | E major | B major :|

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

C# major

B major

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

The bass part isn't very unusual for its era, but there are two features that I found interesting.

For most of the song, the bass arpeggiates the chords it's played beneath. There's the root, third, and fifth, and then it adds a sixth and a flatted seventh before descending, playing the same notes in reverse order. This is a standard feature in early rock and roll bass parts. However, underneath the Bb major, the bass forgoes the flatted seventh and instead plays the root an octave higher. Instead of

which would match the figures played underneath the F major and C major chords, it's

Musically, it makes the song more interesting, but it also demonstrates the character of the snake. This musical figure doesn't match the others in the same way that the snake seems to challenge authority and do whatever he likes. For three of its four occurrences, the lines above this figure describe the snake: "He tracks her down on the way to school," "And he wants to go and have some fun," and "And he's thinkin' 'bout his recreation." The only line above this figure that doesn't mention the snake still has a sort of rebellious element in that it features grammatical errors and mentions the possibility of failing a test: "Well, she got a test, and she don't wanna fail."

At the end of the instrumental section, the song changes keys from F major to F# major. This is a musical illustration of what happens in the third verse:

The snake got the bookworm one fine dayAfter he kisses the bookworm, the snake becomes a bookworm himself, and in order to match this change in his character, the song changes keys. I think there might even be a bit of a musical joke here. The key changes from one flat to six sharps. It becomes "very sharp" in terms of note accidentals, but "very sharp" could also describe an intelligent person, like a bookworm.

And he wouldn't let her get away

Mm, and then he kissed her just one time

And then something happened to his mind

Well, now he sings a different song

He's a-been studyin' all night long

The snake is a bookworm

Similarly, the bass figure underneath the B major chords (formerly Bb major chords) now matches those underneath the F# major and C# major chords. They're all root, third, fifth, sixth, and flatted seventh. Because of the snake's change, the earlier "rebellion" of replacing that flatted seventh with the root played an octave higher has disappeared.

Here's the bass part in full, with the disclaimer that - as always - I might have something wrong:

The other recording of "The Snake and the Bookworm" in my collection (from a compilation titled Essential Early Recordings in The Primo Collection) has the same structure, but it doesn't replace flatted sevenths with roots played an octave higher in the first two verses and, instead of the string of F# notes near the end, continues the arpeggios.

The chords are the same for both versions. It's almost a three-chord song, but in some spots, there are rapid changes to the chord a fourth higher. Each line here represents two measures. The middle chord in each group of three is played for only one beat: the second beat of the second measure.

Introduction:

|: F major | Bb major | F major :|

Verses and Instrumental:

|: F major | Bb major | F major :|

|: Bb major | Eb major | Bb major :||: F major | Bb major | F major :|

C major

Bb major

|: F major | Bb major | F major :|

Verse after key change:

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

|: B major | E major | B major :|

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

C# major

B major

|: F# major | B major | F# major :|

Monday, September 11, 2017

Badfinger's Magic Christian Music

I've been listening to Badfinger's Magic Christian Music with some regularity this year. After listening to it twice last month, I found a number of things to write about. Most are just probable Beatle connections. The liner notes to the edition I have even say that "this is the most Beatles-sounding of the Badfinger releases."

Aside from the artistic resemblances (detailed below), the album has a number of Beatle connections: Badfinger were signed to Apple Corp; Paul McCartney wrote and produced "Come and Get It" and - according to the liner notes - arranged for three Badfinger songs ("Come and Get It," "Carry on Till Tomorrow," and "Rock of All Ages") to be used in the film The Magic Christian, starring Ringo Starr; and about half of the album's tracks were produced by the Beatles' roadie Mal Evans.

Aside from the artistic resemblances (detailed below), the album has a number of Beatle connections: Badfinger were signed to Apple Corp; Paul McCartney wrote and produced "Come and Get It" and - according to the liner notes - arranged for three Badfinger songs ("Come and Get It," "Carry on Till Tomorrow," and "Rock of All Ages") to be used in the film The Magic Christian, starring Ringo Starr; and about half of the album's tracks were produced by the Beatles' roadie Mal Evans.

"Come and Get It"

I learned most of the bass part for "Come and Get It" in February, and I discovered that it has some similarity with the Beatles' "I Saw Her Standing There," although more in tonality than melody (if that makes sense). For the first half of the verses, the bass plays just tonic (Eb), subdominant (Ab), and dominant (Bb) notes, but at the beginning of the line "Did I hear you say that there must be a catch," it goes up a half-step to B natural, an accidental in Eb major. "I Saw Her Standing There" does the same thing with the same accidental (a half-step above the dominant). The bass part there consists of phrases that more or less arpeggiate the tonic (E major), subdominant (A major), and dominant (B major) chords (more on that here), but there's a C natural (an accidental in E major) to accompany the "woo"s. Paul McCartney wrote "Come and Get It" and co-wrote "I Saw Her Standing There," so this tonal similarity seems more than coincidental. McCartney's demo version of "Come and Get It" on the Beatles' Anthology 3 is even in E major, the same key as "I Saw Her Standing There."

"Dear Angie"

I'm not sure if this is intentional or not, but "Dear Angie" seems cast in the same mold as the Beatles' "P.S. I Love You." They're both epistolary songs (both refer to themselves as "this letter"), and both end with "I love you." The phrase "P.S. I love you" shows up more than once in that song, but the "I love you" in "Dear Angie" shows up only at the end. The last section is

Dear Angie

The writing's on the wall

Dear Angie

I love you; you're my all

Guess that's all

Incidentally, the phrase "the writing's on the wall" originally referred to Daniel 5 in the Bible, although it's since acquired a more widespread use.

"I'm in Love"

Again with the probable Beatle connections, I think "I'm in Love" took some inspiration from "When I'm Sixty-Four." The second verse has the lines "Say you will / Love me still / When I'm gray and ninety-three," which bear some resemblance to "Will you still need me / Will you still feed me / When I'm sixty-four." There's a rhyming couplet followed by a line that mentions a specific age.

"Angelique"

The verses of "Angelique" have a steadily strummed guitar and (in later verses) harpsichord arpeggios with notes of equal value. Musically, this is contrasted with an-other section (which I suppose is a bridge) in which the guitar is pluckt, the harpsichord breaks out of its supporting rôle a bit, and there are a number of accidentals. This musical contrast mirrors the contrast in the lyrics. Each verse praises the titular Angelique, ending with "And you're mine / Angelique," but this odd section reveals that the speaker/singer actually isn't in a relationship with Angelique at all:

I'll never be with you

Never, ever touch your hand

So I'll just dream of you

Lonely in my wonderland

Each of the verses represents part of the "wonderland." Because the speaker/singer is imagining a relationship with the incomparable Angelique, those sections have a musical stability, almost a perfection. When the daydream is revealed for what it really is, the music breaks down into accidentals and more erratic rhythms.

I wrote out the notation for the harpsichord part, which might illustrate this better than text alone. I also wrote in the guitar chords. As I mentioned above, the chords aren't strummed during the bridge, so what I have there is extrapolated from the pluckt parts. And - as always - there's the disclaimer I might have something wrong (I'm suspicious that some of the harpsichord part is doubled an octave higher or lower).

I wrote out the notation for the harpsichord part, which might illustrate this better than text alone. I also wrote in the guitar chords. As I mentioned above, the chords aren't strummed during the bridge, so what I have there is extrapolated from the pluckt parts. And - as always - there's the disclaimer I might have something wrong (I'm suspicious that some of the harpsichord part is doubled an octave higher or lower).

"Knocking Down Our Home"

The first line after the introductory section is "I heard the news today," which is the same line (with an "oh boy" at the end) that starts the Beatles' "A Day in the Life." This by itself doesn't seem that strong of a connection, but I think it's likely considering the album's other Beatle connections.

Monday, September 4, 2017

Del Shannon's "I Won't Be There"

Last month, I learned the chords for Del Shannon's "I Won't Be There," and I found some connections between the chords and the lyrics.

First off, here are the chords (although, as always, there's the disclaimer that I might have something wrong):

Introduction:

|: Eb major | C minor | Ab major | Bb major :|

In the second verse, the C major to C minor modulation occurs immediately after the line "He's only gonna break your heart in two." Since major chords are often perceived as happy and minor chords as sad, this modulation musically represents the emotional result of the impending heartbreak.

The song is in three different keys: it starts in Eb major, moves to G major for the first two verses and half of the bridge, and then goes to F# major. To some degree, this peripatetic tonality represents the confusion described in the line "What is my destiny if he's your guy?"

First off, here are the chords (although, as always, there's the disclaimer that I might have something wrong):

Introduction:

|: Eb major | C minor | Ab major | Bb major :|

Following this, there's a chromatic descent with just the root (doubled at the octave) and fifth, so:

D|-8-8-7-7-6-6-

A|-8-8-7-7-6-6-

E|-6-6-5-5-4-4-

A|-8-8-7-7-6-6-

E|-6-6-5-5-4-4-

First verse

G major | E minor | A minor | D major

G major | E minor | C major | D major

G major | G7 | C major | C minor

G major | E minor | A minor | D major

Second verse

G major | E minor | A minor | D major

G major | E minor | C major | D major

G major | G7 | C major | C minor

G major | D major | G major

Bridge

C minor | G major

E minor | F# major

B minor | C# major

Third verse

F# major | D# minor | G# minor | C# major

F# major | D# minor | B major | C# major

F# major | F#7 | B major | B minor

|: F# major | C# major :|

In the second verse, the C major to C minor modulation occurs immediately after the line "He's only gonna break your heart in two." Since major chords are often perceived as happy and minor chords as sad, this modulation musically represents the emotional result of the impending heartbreak.

The song is in three different keys: it starts in Eb major, moves to G major for the first two verses and half of the bridge, and then goes to F# major. To some degree, this peripatetic tonality represents the confusion described in the line "What is my destiny if he's your guy?"

Monday, August 28, 2017

Bobby Darin's "That Lucky Old Sun"

When I listened to a two-CD Bobby Darin compilation about a month ago, I also noticed something about his version of "That Lucky Old Sun." Each verse ends with some variation on "That lucky old sun has nothin' to do / But roll around heaven all day," and in the second and third verses, Darin sings the "around" with melismas. For the second verse, it's Bb G F Eb, and for the third, Bb G Eb.

This articulation has two features. First, there's a musical sense of the "roll[ing] around" because of these extra syllables at various pitches. Second, those extra syllables provide a sense of freedom. Earlier lines in the song that mention work ("Up in the morning, out on the job / Work like the devil for my pay" and "Fuss with my woman, toil for my kids / Sweat till I'm wrinkled and gray") are sung with the same number of syllables they're pronounced with (save for "pay" and "gray," which each have an extra syllable). "That lucky old sun" doesn't have these concerns, so it can "roll around heaven all day" with "nothin' to do," and that freedom is represented by this flexibility with regard to standard syllabic counts.

Listening to the Isley Brothers' version of "Lucky Old Sun" a few years ago, it occurred to me that the lines "Up in the morning, out on the job" and "Fuss with my woman, toil for my kids" exhibit structural parallelism. "Up in the morning" and "out on the job" are parallel, as are "Fuss with my woman" and "toil for my kids." (Even the plea to God to "Show me that river, take me across" has some parallelism.) This parallelism also illustrates the schedule that the speaker/singer operates under. In the same way that these lines are broken into phrases with the same structure, his time is organized according to his labor.

This articulation has two features. First, there's a musical sense of the "roll[ing] around" because of these extra syllables at various pitches. Second, those extra syllables provide a sense of freedom. Earlier lines in the song that mention work ("Up in the morning, out on the job / Work like the devil for my pay" and "Fuss with my woman, toil for my kids / Sweat till I'm wrinkled and gray") are sung with the same number of syllables they're pronounced with (save for "pay" and "gray," which each have an extra syllable). "That lucky old sun" doesn't have these concerns, so it can "roll around heaven all day" with "nothin' to do," and that freedom is represented by this flexibility with regard to standard syllabic counts.

Listening to the Isley Brothers' version of "Lucky Old Sun" a few years ago, it occurred to me that the lines "Up in the morning, out on the job" and "Fuss with my woman, toil for my kids" exhibit structural parallelism. "Up in the morning" and "out on the job" are parallel, as are "Fuss with my woman" and "toil for my kids." (Even the plea to God to "Show me that river, take me across" has some parallelism.) This parallelism also illustrates the schedule that the speaker/singer operates under. In the same way that these lines are broken into phrases with the same structure, his time is organized according to his labor.

Monday, August 21, 2017

Bobby Darin's "Down with Love"

I recently listened to a compilation album of Bobby Darin titled Mighty, Mighty Man, and I noticed something about "Down with Love" (from the album This Is Darin, which happens to be the only original Bobby Darin album I have).

Darin articulates a number of phrases in ways that draw attention to "down." The "Down" that starts the second verse is sung with a descending glissando (I think it's from C to Eb, but I found it a bit difficult to pinpoint). "Down with Cupid" in the bridge is sung to a descending phrase both times. It's even chromatic, which seems to emphasize the descent: Eb, D, Db, C. The "Down with love" that starts the third verse (a repetition of the second verse) is sung to the descending phrase Eb C Bb. Finally, the "Down" in the last "Down with love" is sung with a melisma, starting with a Bb and moving through various notes down to Eb.

For what it's worth, a few years ago, I noticed that the line "Down with songs that moan about night and day" refers to the song "Night and Day" and wrote a short post about it.

Darin articulates a number of phrases in ways that draw attention to "down." The "Down" that starts the second verse is sung with a descending glissando (I think it's from C to Eb, but I found it a bit difficult to pinpoint). "Down with Cupid" in the bridge is sung to a descending phrase both times. It's even chromatic, which seems to emphasize the descent: Eb, D, Db, C. The "Down with love" that starts the third verse (a repetition of the second verse) is sung to the descending phrase Eb C Bb. Finally, the "Down" in the last "Down with love" is sung with a melisma, starting with a Bb and moving through various notes down to Eb.

For what it's worth, a few years ago, I noticed that the line "Down with songs that moan about night and day" refers to the song "Night and Day" and wrote a short post about it.

Monday, August 14, 2017

Unit 4+2's Singles As & Bs

For Christmas a few years ago, I got Unit 4+2's Singles As & Bs. At the time, I knew only "Concrete and Clay" (I knew "You Ain't Going Nowhere" via the Byrds' version, but I hadn't heard Unit 4+2's), but the album quickly became one of my favorites over the course of the following year. I started drafting a post about a year after I got it, but then I sort of forgot about it (the post). I figured I'd finally finish it.

"When I Fall in Love"

The "fall in love" in the titular line is sung to a descending phrase (E D# B, I think), so there's a musical representation of the falling, even if it is only metaphorical.

When I originally transcribed the song, I rendered a pair of lines as "And too many moonlight kisses / Seem to cool in the warmth of the sun," but when I looked over my transcription a few weeks later, I realized that it could also be "And too many moonlight kisses / Seem too cool in the warmth of the sun." In the first rendering, "to cool" is an infinitive; in the second, "too cool" is an adverb/adjective combination modifying the "kisses" from the previous line. That second rendering is probably what's intended because then there's a parallelism between "too many" and "too cool." Still, it's one of those great features that's ambiguous when heard but has to fall one way or the other when it's written out.

I also noticed something about the first two lines of the last verse: "And the moment I can feel that / You feel that way too." There's a caesura after the "that" in the second line, so even though the two "that"s function differently (the first is an indicator of an indirect statement and the second is a demonstrative adjective modifying "way"), because of that pause there, it briefly sounds like there's a parallelism between "I can feel that" and "You feel that." There's a pairing there, which is appropriate for a song about falling in love.

I also noticed something about the first two lines of the last verse: "And the moment I can feel that / You feel that way too." There's a caesura after the "that" in the second line, so even though the two "that"s function differently (the first is an indicator of an indirect statement and the second is a demonstrative adjective modifying "way"), because of that pause there, it briefly sounds like there's a parallelism between "I can feel that" and "You feel that." There's a pairing there, which is appropriate for a song about falling in love.

"You've Got to Be Cruel to Be Kind"

The titular phrase - slightly altered - comes from Shakespeare's Hamlet. In Act 3, Scene 4, Hamlet says, "I must be cruel, only to be kind" (III.iv.199). The song doesn't really have anything to do with Hamlet, but that's the origin of that phrase."I Won't Let You Down"

The line "Hurtin' in my body and the sweat on my brow now" in the first and third verse (it's the same verse repeated) references Genesis 3, if only indirectly. Because of the fall into sin, Adam has to work in the fields in order to eat, and in verse nineteen, God tells him, "By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food." It's basically the same as the phrase in the song, but since it's become a common phrase, I don't think it's really intended as a Biblical reference.

"3.30"

One of the verses has the lines "And again I try / Not to reason why." Like the allusions I found in the other songs, I don't think this is intended as anything more than just the borrowing of a phrase, this time from Tennyson's "The Charge of the Light Brigade." In the third stanza, one of the lines is "Theirs not to reason why."

---&---

For my Collection Audit project, I've also written about "I Will" (which quotes a Bach violin partita) and "A Place to Go" (which has a lyrically significant key change).

Friday, August 11, 2017

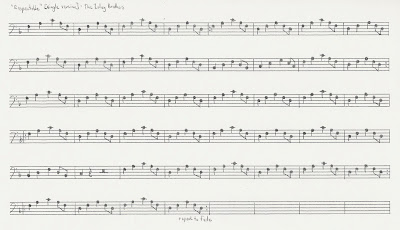

The Isley Brothers' "Respectable" [single version]

I recently listened to a two-CD set of the Isley Brothers, and the bass part for the single version of "Respectable" sounded really easy, so I figured it out and notated it:

I considered writing in the chords, but since they last for only one measure each, I thought it would make the notation look too cluttered. The bass part just arpeggiates the chords played above it: F major, D minor, Bb major, and C major.

The F major/D minor arpeggiations continue until the fade out, so I put four measures of them within repeat signs, but the fade out actually doesn't last much longer than that.

I considered writing in the chords, but since they last for only one measure each, I thought it would make the notation look too cluttered. The bass part just arpeggiates the chords played above it: F major, D minor, Bb major, and C major.

The F major/D minor arpeggiations continue until the fade out, so I put four measures of them within repeat signs, but the fade out actually doesn't last much longer than that.

Monday, August 7, 2017

The Moody Blues' "Lovely to See You"

A few weeks ago, the Moody Blues' "Lovely to See You" was in my head when I woke up (although, at the time, I hadn't listened to On the Threshold of the Dream [the album it's on] for about three months). The bridge is what was in my head:

In any case, this image of "empires... turn[ing] back to sand" reminded me of Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Ozymandias." It has the same image of a once-vast domain that has since "decay[ed]" so that only "lone and level sands" and fragments of a statue remain.

There really isn't anything else in "Lovely to See You" that seems connected to "Ozymandias," but between the same image of "empires... turn[ing] back to sand" and the land(s)/sand rhyme (which is also in "Ozymandias"), I think Shelley's poem might have influenced "Lovely to See You," if only slightly.

Tell us what you've seen in faraway forgotten landsThat's how it's rendered in the liner notes, although - appropriate to their having been forgotten - the word "lands" is cut off:

Where empires have turned back to sand

In any case, this image of "empires... turn[ing] back to sand" reminded me of Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Ozymandias." It has the same image of a once-vast domain that has since "decay[ed]" so that only "lone and level sands" and fragments of a statue remain.

There really isn't anything else in "Lovely to See You" that seems connected to "Ozymandias," but between the same image of "empires... turn[ing] back to sand" and the land(s)/sand rhyme (which is also in "Ozymandias"), I think Shelley's poem might have influenced "Lovely to See You," if only slightly.

Monday, July 31, 2017

The Hollies' "Do the Best You Can"

After listening to the Hollies' first five albums recently, I decided to listen to the three-disc compilation 30th Anniversary Collection 1963-1993. Even before I listened to it, I realized something about "Do the Best You Can," specifically this section:

If you leave your car

And you're not going far

Remember what time to be back

If it slips your mind

I'm sure in time you'll find

A Rita waiting in a mac

Instead of the implied "meter maid," there's just the name "Rita." I'm pretty sure this is something of a reference to the Beatles' "Lovely Rita" from Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, specifically its recurring line "Lovely Rita, meter maid." "Do the Best You Can" seems to assume familiarity with "Lovely Rita," and uses the name "Rita" as a short-hand for "meter maid."

I checkt the chronology, and it works out. According to Mark Lewisohn's The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Sgt. Pepper was released on 1 June 1967, and according to the liner notes of 30th Anniversary Collection, "Do the Best You Can" was released over a year later. It was the A side of singles in the U.S. and West Germany in July 1968, and the B side of "Listen to Me" in the U.K. in September 1968.

I checkt the chronology, and it works out. According to Mark Lewisohn's The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Sgt. Pepper was released on 1 June 1967, and according to the liner notes of 30th Anniversary Collection, "Do the Best You Can" was released over a year later. It was the A side of singles in the U.S. and West Germany in July 1968, and the B side of "Listen to Me" in the U.K. in September 1968.

Monday, July 24, 2017

The Hollies' "Pay You Back with Interest"

While listening to the Hollies' For Certain Because... (for only the second time) last month, I noticed something about the bridge of "Pay You Back with Interest" (which I was already fairly familiar with because it's also included on the 30th Anniversary Collection, which I've had for years).

The lead vocals are:

The lead vocals are:

How cold is my room without your love beside me

We look at the same old moon, but you're not here beside me

The backing vocals are more or less the same as the lead vocals, just with fewer words:

How cold is my room [be]side me

Lookin' at the moon [be]side me

Significantly, some of the words from the lead vocals that are left out in the backing vocals are "your love" and "you." There's an omission in the backing vocals in the same way that the singer/speaker is absent from his love while he's "travelin'" and "wanderin'."

Monday, July 17, 2017

The White Stripes' "The Union Forever"

A couple months ago, I listened to a ten-CD set of Duke Ellington for the first time. The lines "It can't be love / For there is no true love" in "In a Mizz" caught my ear. I knew these same lines were in a song on the White Stripes' White Blood Cells, although I had to look up which one specifically. It's "The Union Forever," which starts with these same lines repeated:

It can't be love

For there is no true love

It can't be love

For there is no true love

The situations in the two songs are somewhat comparable. In the verses of Ellington's song, the speaker/singer constantly wonders "what it is / That's keeping me in a mizz." There, the "it can't be love" line appears in the bridge. At the end of the White Stripes' song, the speaker/singer recalls that his girlfriend "cried the union forever / But that was untrue, girl / 'Cause it can't be love." Both seem upset about a lost love, but neither wants to admit that the relationship was ever that strong.

I knew about Jack White's interest in old blues records because of the vinyl re-releases that his Third Man Records put out. Ellington is more jazz than blues, but between White's interest in older music and the fact that the lines are exactly the same, I think this is an intentional quotation of "In a Mizz."

Monday, July 10, 2017

Billy Joel's "Piano Man"

A couple weeks ago, I was thinking about Billy Joel's "Piano Man," and I realized something about this verse:

He says, "Son, can you play me a memory

"I'm not really sure how it goes

"But it's sad, and it's sweet, and I knew it complete

"When I wore a younger man's clothes"

The "complete" in the third line is a flat adverb, devoid of its usual -ly ending. Part of this might be to avoid an overload of syllables in that line. More likely, it's so that there's a perfect internal rhyme between "sweet" and "complete" (as there is between "joke" and "smoke" in a later verse).

Aside from technical considerations, as a flat adverb, "complete" indicates the degradation of the old man's memory. He himself says that he's "not really sure how it goes." In the same way that his memory isn't intact, neither is the word completely.

Monday, July 3, 2017

The Byrds' "The Christian Life"

Last month I learned the chords for the Byrds' "The Christian Life" from Sweetheart of the Rodeo. After I learned them, I noticed some connections between the chords and the lyrics.

The chord progression has three sections. The introduction:

D major | A major | D major | G major

G major | D major | A major | D major | D major

The verses (sometimes halved):

D major | A major | D major | D major

D major | A major | E major | A major

D major | A major | D major | G major | G major

G major | D major | A major | D major | D major

The chord progression has three sections. The introduction:

D major | A major | D major | G major

G major | D major | A major | D major | D major

The verses (sometimes halved):

D major | A major | D major | D major

D major | A major | E major | A major

D major | A major | D major | G major | G major

G major | D major | A major | D major | D major

And the bridges and instrumental sections:

A major | A major | G major | D major

A major | A major | G major | A major | A major

One of the first things I noticed about the song after I learned the chords is that it's in 3/4 time. Since the song is about "The Christian life," the three beats to the bar could easily represent the three figures of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Aside from a single E major, the chords are just the tonic (D major), subdominant (G major), and dominant (A major), so there's an-other instance of three. The song is based on musical threes, just as the singer/speaker of the song - who "like[s] the Christian life" - has "built his house on the rock" (Matthew 7:24-27) of the Trinity.

The E major chord contains a G#, which is an accidental in the key of D major. Significantly, the E major (with its accidental) is beneath the lyrics "whole world of" in the line "They say I'm missing a whole world of fun." That whole world of fun contains "things I despise" (that is, sin), and that accidental represents them. The "whole world of fun" is separate from the Christian life in the lyrics, and also in the music, since it's founded on something other than the tonic, subdominant, or dominant.

The first two lines of each verse ("My buddies tell me that I should have waited / They say I'm missing a whole world of fun" and "My buddies shun me since I turned to Jesus / They say I'm missing a whole world of fun") and the first line of the bridge ("I won't lose a friend by heeding God's call") are each four measures long. Since each measure has three beats, each line is a total of twelve beats. Twelve is also an important number in Christianity. For example, there are twelve Tribes of Israel and twelve apostles. Admittedly, this doesn't seem as significant as the other features I've noted, but I thought I'd mention it all the same.

Friday, June 30, 2017

Peter & Gordon's "Lady Godiva"

This month, I learned the bass/low brass part for Peter & Gordon's "Lady Godiva" (I'm not sure if the low brass instrument is tuba or euphonium). Certainly for the first few measures, they play the same thing, and I think they play the same thing throughout the rest of the song, but it's sometimes a bit difficult to tell. Some of the subtleties in my notation might be more brass than bass just because it's easier to pick out in the mix, although - as always - there's the disclaimer that I might have something wrong.

Monday, June 26, 2017

"Edelweiss" (from The Sound of Music)

A couple weeks ago, I learned the melody for "Edelweiss" from The Sound of Music. I figured it out and notated it from memory, but when I checkt the recording on The Sound of Music soundtrack, I discovered that I even had it in the right key: Bb major. I standardized the note values a bit compared to how Christopher Plumber sings it, and I might have been a bit liberal with the rests:

After playing this a few times, I realized something about the melody to which "Blossom of snow may you bloom and grow / Bloom and grow forever" is sung:

The musical phrase to which each "Bloom and grow" is sung ascends, with the second starting higher than the first:

Individually, each musical phrase portrays growth through that ascent, and the effect is compounded because the second starts at a higher pitch than the first.

The second thing I noticed about this phrase is that the "forever" is sung to six beats spanning three measures. It starts with a quarter note (on the third beat of the measure), continues into the next measure with a dotted half note, and then ends in a third measure with a half note. This "forever" has more syllables than any other word in the song (aside from "edelweiss" itself) and spans more measures than any other word (every instance of "edelweiss" fits within two measures). The "forever" in the line "Bless my homeland forever" has the same note values distributed across measures in the same way; it's just sung to different pitches. That these "forever"s are sung spanning three measures demonstrates the long period of time for which the edelweiss flower is supposed to "bloom and grow" and "bless my homeland."

After playing this a few times, I realized something about the melody to which "Blossom of snow may you bloom and grow / Bloom and grow forever" is sung:

The musical phrase to which each "Bloom and grow" is sung ascends, with the second starting higher than the first:

Individually, each musical phrase portrays growth through that ascent, and the effect is compounded because the second starts at a higher pitch than the first.

The second thing I noticed about this phrase is that the "forever" is sung to six beats spanning three measures. It starts with a quarter note (on the third beat of the measure), continues into the next measure with a dotted half note, and then ends in a third measure with a half note. This "forever" has more syllables than any other word in the song (aside from "edelweiss" itself) and spans more measures than any other word (every instance of "edelweiss" fits within two measures). The "forever" in the line "Bless my homeland forever" has the same note values distributed across measures in the same way; it's just sung to different pitches. That these "forever"s are sung spanning three measures demonstrates the long period of time for which the edelweiss flower is supposed to "bloom and grow" and "bless my homeland."

Friday, June 23, 2017

Roy Orbison's "I Give Up"

Last week I listened to a Roy Orbison album (The Essential Sun Years), and I learned the chords for "I Give Up." A couple days later, I recorded a version. Since it's just voice and guitar, it was relatively straight forward. I recorded the vocal and guitar parts at the same time, so when I later discovered a few extraneous noises in the vocal track, I couldn't really cut them out. The vocal microphone still pickt up the guitar in the background, so cutting parts out of that track was too noticeable. Still, I don't think I did too badly. I followed the original as closely as I could, including the few minor lyrical differences between repetitions of the bridge and final verse.

Here are the chords:

Verses:

E major | B major

B major | E major

E major | B major

A major | B major | E major (E7 to second bridge)

Bridge

|: A major | E major :|

F# major | B major

Coda

E major | A major | E major

Here are the chords:

Verses:

E major | B major

B major | E major

E major | B major

A major | B major | E major (E7 to second bridge)

Bridge

|: A major | E major :|

F# major | B major

Coda

E major | A major | E major

Monday, June 19, 2017

The Byrds' "I Am a Pilgrim"

A couple years ago, I wrote a post about the Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo in which I mentioned some Biblical references in "I Am a Pilgrim." I wrote that the lines "If I can just touch the hem of His garment, good Lord / Then I'd know He'd take me home" reference the woman "healed from a discharge of blood after touching only the fringe of Jesus' garment" recounted in Matthew 9, Mark 5, and Luke 8.

Recently, though, I read part of Matthew 14 and found an-other passage that could just as well be the referent for those lines. After feeding the five thousand and walking on the water, Jesus (with His disciples) "came to land at Gennesaret. And when the men of that place recognized him, they sent around to all that region and brought to him all who were sick and implored him that they might only touch the fringe of his garment. And as many as touched it were made well" (Matthew 14:34-36). There's a parallel account in Mark 6:53-56.

Where both of these Scriptural accounts deal with healing rather than - as it is in "I Am a Pilgrim" - being taken home (that is, taken to Heaven, "that yonder city... not made by hand... Over on that other shore"), they do both mention "touch[ing] the fringe of his garment," which is also what's in the song.

Recently, though, I read part of Matthew 14 and found an-other passage that could just as well be the referent for those lines. After feeding the five thousand and walking on the water, Jesus (with His disciples) "came to land at Gennesaret. And when the men of that place recognized him, they sent around to all that region and brought to him all who were sick and implored him that they might only touch the fringe of his garment. And as many as touched it were made well" (Matthew 14:34-36). There's a parallel account in Mark 6:53-56.

Where both of these Scriptural accounts deal with healing rather than - as it is in "I Am a Pilgrim" - being taken home (that is, taken to Heaven, "that yonder city... not made by hand... Over on that other shore"), they do both mention "touch[ing] the fringe of his garment," which is also what's in the song.

Friday, June 16, 2017

Cliff Richard's "Here Comes Summer"

Since summer starts next week, I thought I'd post the chords to Cliff Richard's "Here Comes Summer," which I actually figured out in early winter last year.

Verses:

|: D major | B minor | E minor | A major :| D major

Bridge:

G major | D major | G major | A major

~key change to Eb major~

Verses:

|: Eb major | C minor | F minor | Bb major :| Eb major

Bridge:

Ab major | Eb major | Ab major | Bb major

Verses:

|: D major | B minor | E minor | A major :| D major

Bridge:

G major | D major | G major | A major

~key change to Eb major~

Verses:

|: Eb major | C minor | F minor | Bb major :| Eb major

Bridge:

Ab major | Eb major | Ab major | Bb major

Monday, June 12, 2017

The Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed

Over the last two months I listened to the Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed every Thursday. Originally, I'd intended to keep this up until the end of the year, but I got busy with other projects and reconsidered it. In any case, I found a few things to write about.

"Evening: The Sun Set/Twilight Time"

During the bridge of "Twilight Time," there's the line "Building castles in the air." The melody to which this is sung ascends, representing the increasing height of the castles as they're built:

I should mention that I guessed on the key, but whatever key "Twilight Time" is in does have at least two flats. There's an Eb in the vocal melody and a Bb in the recurring piano phrase.

"The Night: Nights in White Satin"

During the line "Impassioned lovers wrestle as one" in the closing narration, there are tremolos in the strings, apparently to musically represent that "wrestl[ing]."

Monday, June 5, 2017

Carpenters' Ticket to Ride

Last month I listened to the Carpenters' Ticket to Ride and found some things to write about.

"Your Wonderful Parade"

When I listened to the album a few other times, the phrase "of the people, by the people, and for the people" in the spoken introduction sounded familiar to me. I couldn't place it though, so I eventually just lookt it up. It's from Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

"Get Together"

I have four versions of this song (with various titles) in my music collection, and three of the four sing the "hand" in the line "It's in your trembling hand" (or some variation of that) with a melisma. It's sung to more than one note to musically illustrate the trembling. The Dave Clark Five don't include this verse in their version ("Everybody Get Together"), but Jefferson Airplane ("Let's Get Together") sing it to the phrase C B A; the Youngbloods to the phrase C# B; and the Carpenters to the phrase Bb A G. However, the Carpenters go a bit further with this portrayal of trembling: the entirety of the vocal for the verses has a wavering effect (I'm assuming it's done through a Leslie speaker, but I didn't find anything to confirm this).

"Turn Away"

The end of the line "Or are you afraid that I'll bring you down" descends; "bring you down" is sung to the phrase A G F#. The backing vocals after that line echo "Bring you down," and while one of the vocal parts is just sung to F# notes, the other part descends, like the line in the lead vocal. It starts on a B, but then goes to an A#. Because the song is in D major, that A# is an accidental. Musically, then, the misstep of being brought down is represented not only with a descending melody but also with an accidental.

Monday, May 29, 2017

Three Dog Night's "Joy to the World"

A couple weeks ago, I happened to think of Three Dog Night's "Joy to the World" (from the album Naturally), specifically the line "And he always had some mighty fine wine," and I realized that it uses some poetic devices.

Initially I noticed just the assonance among "mighty," "fine," and "wine." They all have long I sounds. When I typed this out just to make a note of it, I also realized that there's internal rhyme with "fine" and "wine." Along with just making the lyrics sound euphonious, the elevated language gives an-other indication of the high quality of the wine it's describing.

Initially I noticed just the assonance among "mighty," "fine," and "wine." They all have long I sounds. When I typed this out just to make a note of it, I also realized that there's internal rhyme with "fine" and "wine." Along with just making the lyrics sound euphonious, the elevated language gives an-other indication of the high quality of the wine it's describing.