Because I'd been reading a book about Handel when I started

the Classical Music Queue, Messiah ended up being in it a lot. There were two weeks where I listened to it (or excerpts from it) everyday, so I started to become fairly familiar with it. Before this year, I'd listened to it only five times.

I started finding a lot to say about it, but I should note that this is in no way complete and isn't meant to be. Mostly, it's just a record of the things I've noticed after listening to it (or excerpts from it) thirty-nine times in three months.

I found some of the specific Biblical texts used (mostly by happenstance), and I include them only to show which ones I found. I'm sure they're all listed somewhere, but I wanted to find them for myself if I could. The translations might differ slightly. For instance, Messiah has "the dead shall be raised incorruptible" where my Bible has "the dead will be raised imperishable."

The only complete recording I have is by Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, and I also have some excerpts by the Royal Music College Edinburgh. I looked through the scores available on

IMSLP, but I couldn't find one that really matched, so some of the notation I have might vary.

Part I

1. Symphony

2. Comfort ye my people

"Comfort, comfort my people, says your God. Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her that her warfare is ended, that her iniquity is pardoned, that she has received from the LORD's hand double for all her sins. A voice cries: 'In the wilderness prepare the way of the LORD; make straight in the desert a highway for our God.'" - Isaiah 40:1-3

I didn't notice this until I looked at the notation, but the first syllables of one instance of "iniquity" and "pardoned" have accidentals:

The accidental on "iniquity" pretty clearly indicates the error inherent in sin, but the accidental on "pardoned" took me a while to suss out. It might just be there to make the melody that Handel wanted (as could the accidental on "iniquity"), but it might also be indicative of redemption: in the same way that Christ had to take on sin to redeem people from their sins, "pardoned" has an accidental like "iniquity." Musically, it illustrates what is sung later: "with his stripes we are healed."

3. Ev'ry valley shall be exalted

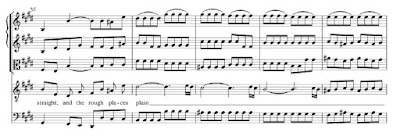

"'Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain.'" - Isaiah 40:4

There are some interesting musical figures to which "crooked," "straight," "rough," and "plain" are set. Generally, "crooked" and "rough" are set over a multitude of notes and notes of various intervals, and "straight" and "plain" are set over fewer notes that are closer together. So "crooked" and "rough" sound crooked and rough when sung, and "straight" and "plain" sound straight and plain.

4. And the glory of the Lord

"'And the glory of the LORD shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the LORD has spoken.'" - Isaiah 40:5

5. Thus saith the Lord of hosts

"Behold, I send my messenger, and he will prepare the way before me. And the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple; and the messenger of the covenant in whom you delight, behold, he is coming, says the LORD of hosts." - Malachi 3:1

Similar to the settings of "crooked," "straight," et al in No. 3, here, there's a programmatic aspect with "shake." It's separated into many notes to give the impression of shaking.

At one point, "the heavens" has an rising melody, and "the earth" a falling one, as if to reflect the relative positions of each (the heavens are above the earth).

I didn't notice this until I started listening to Messiah while looking at the notation, but there's also a part where the instruments start playing after a rest, corresponding to "come" in "he shall come." It's like they're meant to emphasis the coming.

6. But who may abide the day of His coming

"But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears? For he is like a refiner's fire and like fullers' soap." - Malachi 3:2

7. And he shall purify the sons of Levi

"He will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the sons of Levi and refine them like gold and silver, and they will bring offerings in righteousness to the LORD." - Malachi 3:3

8. Behold, a virgin shall conceive

9. O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion

"Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the LORD has risen upon you." - Isaiah 60:1

The "lift[ing] up" mentioned in this section is emphasized by a rising melody.

Similarly, the "arise"s have an upward trend.

10. For behold, darkness shall cover the earth

"For behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and thick darkness the peoples; but the LORD will arise upon you, and his glory will be seen upon you." - Isaiah 60:2

An-other rising "arise"

11. The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light

12. For unto us a child is born

"For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace." - Isaiah 9:6

13. Pifa

14. There were shepherds abiding in the fields

"And in the same region there were shepherds out in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And an angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were filled with fear." - Luke 2:8-9

The shape of this phrase is interesting. Visually (and I suppose also audibly), it goes really well with the text. "Keeping watch over their flock by night" forms an arc, as if to symbolize the shepherds' watching, and the highest note in the phrase occurs over "flock," the object over which they're watching.

15. And the angel said unto them

"And the angel said to them, 'Fear not, for behold, I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord.'" - Luke 2:10-11

16. And suddenly there was with the angel

"And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying," - Luke 2:13

17. Glory to God in the highest

"'Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!'" - Luke 2:14

There are actually two things here that emphasize the distance between "the highest" and "on earth." The "highest" is at a higher pitch than "on earth," but it's also sung by the higher registers (sopranos and altos [and also tenors]) where "on earth" is sung by the lower registers (tenors and basses).

18. Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion

19. Then shall the eyes of the blind be opened

20. He shall feed his flock like a shepherd

21. His yoke is easy

Part II

22. Behold the Lamb of God

"The next day he [John] saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, 'Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!'" - John 1:29

One of the instances of "away" splits the two syllables into the interval of a fifth, which helps to underscore the completeness or the distance to which "the sin of the world" is taken away.

23. He was despised and rejected of men

An-other thing I didn't notice until I started following along with the notation is the cross-like figure inscribed here with "he was despised."

I first ran across this cross-inscribing feature in John Eliot Gardiner's

Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, where he points out how Bach does this in

Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4:

I'm not sure if it was Handel's intent here (I don't know how well-known this cross-inscription technique was in the 1700s), but it does provide an example of one of the forms in which Christ was despised - the crucifixion.

24. Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows

25. And with his stripes we are healed

26. All we like sheep have gone astray

The ends of some of the "have gone astray" phrases sort of trail off to mirror the wandering.

Once I started looking into the notation, I also noticed that in some places, the melodies of the various parts are going in opposite directions ("we have turned ev'ry one to his own way"). Some are going up while other are going down.

27. All they that see him laugh him to scorn

After the first line of this section, there are figures in the violin part that sound like laughing:

28. He trusted in God that he would deliver him

This is an-other thing I didn't notice until I started looking into the notation: the choral parts are written in such a way that "deliver" and "delight" are sometimes sung simultaneously. I'm not sure if there's any religious meaning behind this, but there's at least a poetic one, since "deliver" and "delight" exhibit consonance.

Later in this section, there's a melisma on one of the "delight"s so that it sounds like a laugh. It's similar to the previous section (All they that see him laugh him to scorn) in that it's a musical effect to portray laughing and it's an-other way in which Christ was mocked.

29. Thy rebuke hath broken his heart

30. Behold and see if there be any sorrow

31. He was cut off

32. But thou didst not leave his soul in hell

I'm not sure if it's the source for the text here, but there is some similarity between this and Psalm 16:10 - "For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption."

33. Lift up your heads, O ye gates

"Lift up your heads, O gates! And be lifted up, O ancient doors, that the King of glory may come in. Who is this King of glory? The LORD, strong and mighty, the LORD, mighty in battle! Lift up your heads, O gates! And lift them up, O ancient doors, that the King of glory may come in. Who is this King of glory? The LORD of hosts, he is the King of glory!" - Psalm 24:7-10

34. Unto which of the angels

35. Let all the angels of God worship Him

36. Thou art gone up on high

37. The Lord gave the word

38. How beautiful are the feet

39. Their sound is gone out

40. Why do the nations so furiously rage together

"Why do the nations rage and the peoples plot in vain? The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD and his Anointed, saying," - Psalm 2:1-2

I didn't notice this until looking at the notation, but there are tremolos during this section, apparently to reflect the "rag[ing] together" of the nations.

41. Let us break their bonds asunder

"'Let us burst their bonds apart and cast away their cords from us.'" - Psalm 2:3

Some of the "away"s in this section - like the "away" in No. 22 - also have large intervals between the two syllables (A to F, C to F, and D to Bb), to underscore the distance to which the yokes should be cast.

Later in the section, Handel sets "bonds" & "break" and "bonds" & "asunder" against each other, like the "deliver"s and "delight"s in No. 28.

42. He that dwelleth in heaven

"He who sits in the heavens laughs; the Lord holds them in derision." - Psalm 2:4

43. Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron

"You shall break them with a rod of iron and dash them in pieces like a potter's vessel." - Psalm 2:9

44. Hallelujah

A few of the "and He shall reign" phrases inscribe the cross figure, apparently to show that through Christ's crucifixion and resurrection, God has power over death:

Part III

45. I know that my Redeemer liveth

46. Since by man came death

"For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive." - 1 Corinthians 15:21-22

If I posted an example of the notation for this, I'd end up posting the whole section, which I'd rather not do. There's a distinction made between "Since by man came death" (

grave) and "By man came also the resurrection" (

allegro). Later, the same is done for "For as in Adam all die" (

grave again) and "Even so in Christ shall all be made alive" (

allegro again).

It wasn't specified in the version of the notation that I looked through, but in the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields recording, these parts are also differentiated by dynamics. The

grave parts are

piano (perhaps even

pianissimo; I couldn't understand the words until I read them), and the

allegro parts are

forte.

47. Behold, I tell you a mystery

"Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet."

- 1 Corinthians 15:51-52a

48. The trumpet shall sound

"For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality." - 1 Corinthians 15:52b-53

It's pretty obvious, but I'll mention it anyway: taking a note from the text, there's a trumpet in this section (the top line of music). Also, "the dead shall be raised" conforms to a rising melody.

I don't think I noticed this until looking at the notation, but one of the "we shall be changed" phrases also inscribes the cross figure, apparently illustrating that it's through believing in Christ's crucifixion and resurrection that we are changed:

49. Then shall be brought to pass

"When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written: 'Death is swallowed up in victory.'" - 1 Corinthians 15:54

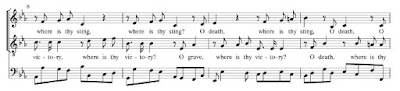

50. O death, where is thy sting

"'O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?' The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law." - 1 Corinthians 15:55-56

Handel's setting of this is great in pulling apart these phrases so that it can be seen (or heard) how parallel they are.

They're sung almost simultaneously, so that "death" and "grave" match up, as do "where is thy sting?" and "where is thy victory?". I looked into the source for this text a bit more, and - apparently - it's a quotation of Hosea 13:14: "Shall I ransom them from the power of Sheol? Shall I redeem them from Death? O Death, where are your plagues? O Sheol, where is your sting? Compassion is hidden from my eyes." I'm not sure if it's the case here (although it seems like it is), but some sections of the Old Testament (Psalms in particular) use this parallel structure, where almost the same thing is said in two different ways. There are some other parts of the Messiah that are structured like this, but because it's a duet, the setting of "O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?" is exemplary in musically illustrating that structure.

51. But thanks be to God

"But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ." - 1 Corinthians 15:57

52. If God be for us, who can be against us

"If God is for us, who can be against us?" - Romans 8:31b

"Who shall bring any charge against God's elect? It is God who justifies. Who is to condemn? Christ Jesus is the one who died - more than that, who was raised - who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us." - Romans 8:33-34

53. Worthy is the Lamb, Amen

"[Many angels were] saying with a loud voice, 'Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!' And I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all that is in them, saying, 'To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb be blessing and honor and glory and might forever and ever!' And the four living creatures said, 'Amen!' and the elders fell down and worshipped" - Revelation 5:12-14